#MFScience survey – the results are in

The 24 hour flash poll* was simply this – find a non-scientist and ask them to name famous scientists: one male, one female. Then we sat back as the answers came in. And they did! Thick and fast, mostly through Twitter but also via our Facebook page – and by generally bugging our own family and friends.

And the winner is…..

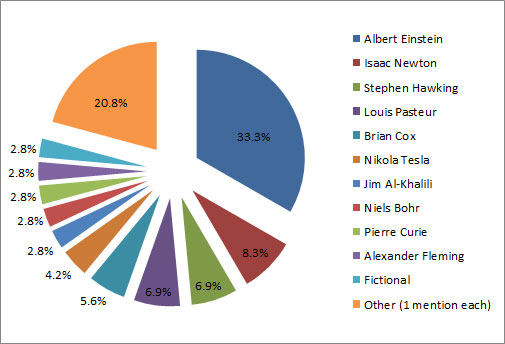

We confess to having had a hunch about which female scientist would come out in the lead. Marie Curie was our Usain Bolt with 61.3% of the share and the others ate her dust: Rosalind Franklin was next with 8.1% of the mentions. We saw a similar pattern with the male scientists. Albert Einstein was far out in front with 33.3% of mentions and there was a sharp drop-off before Isaac Newton got his 8.3% look in.

Looking at the way the numbers fall, the contrast between Curie’s lead and Einstein’s seems to be because people can name more male scientists overall. That is, the female mentions were distributed amongst fewer names, so Curie has less competition. Out of the male scientists we see 25 original names, whereas there are 14 in the female group. We’ve subtracted fictional characters from this count! Yes, we got some of those….

The other reason for Curie’s massive lead is that we see more repeats in the male scientist group: 40% of the men were mentioned more than once, compared to 28.6% of the women. When selecting a male scientist to mention, it seems like the non-scientists we asked had a greater pool of men at their fingertips.

“That woman who…..” We excluded something else from our ‘unique mentions’ count, but only for the women because it just didn’t come up for the men. We had 3 responses that were a description of a woman scientist. These were: “that woman who didn’t get recognition for her work on DNA”, ‘that cancer lady” and “the lady who invented Kevlar”. We’ll help out by telling you that we think they meant: Rosalind Franklin, Marie Curie (because it is well known that she developed cancer as a result of her work on radioactivity) and Stephanie Kwolek.

Er, can I pick you? Something else to note is that we didn’t get an equal number of responses for male and female scientists. Overall, nine didn’t name a woman at all. Only one didn’t name a man. Three people tried to choose the woman scientist who asked them the poll question! Two responses came with an admission that they couldn’t think of a female scientist off the top of their heads, and didn’t want to cheat.

We loved (but had to exclude) a happily rebellious voter who gave us 5 females (Emile du Chatelet, Ada Lovelace, Marie Curie, Lise Meitner, Fabiola Gianotti) but joked that they couldn’t think of any males.

Wanted: dead or alive When we break the list down by number of mentions, 20.8% of the male and 14.5% of the female went to living scientists. Pretty similar, but it would be interesting to see how those numbers look with a larger sample. Overall, historical figures greatly outnumber living scientists. This isn’t surprising: scientists are recognised when they make a significant and lasting contribution to their field. That’s something that often needs historical context.

Looking a little closer, we learn that 3 out of 7 of the living male scientists were mentioned more than once: Stephen Hawking, 5 mentions; Brian Cox, 4 mentions; and Jim Al-Khalili, 2 mentions. Only 1 out of 8 of the living female scientists was mentioned more than once. This was Jocelyn Bell Burnell: she was mentioned twice.

We asked for famous scientists and everyone on our list has made a great contribution. The majority of mentions went to the great thinkers and innovators we have learned about over the years. But we believe that people also know Stephen Hawking, Brian Cox and Jim Al-Khalili because they see and hear from them on a regular basis. They are visible.

That’s what we’re trying to do with the ScienceGrrl calendar. To reflect the many women doing great work in the lab and to help the names of female scientists roll off the tongue. Why? A 2011 survey by GirlGuidingUK found that 60% of girls thought a lack of female role models was a major reason for low female entry into STEM careers. We can keep discussing how and where these women are most effectively seen – on the TV, in our calendar, through their writing, through school mentorship programmes, etc – and we plan to. But one thing’s for certain: you can’t have an invisible role model.

* Kind of like asking your mates down the pub, but on a larger scale. And just as rigorous.